Lessons in Family Business Sustainability from Switzerland

Co-planned with Switzerland Global Enterprise, BFI@SMU’s 6th learning journey1 gave our business families the opportunity to meet and learn from their counterparts in Switzerland about transgenerational practices and innovation. From the 7th to 12th of November, 15 business families from Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Vietnam visited well-known family firms covering a wide array of industries including domestic appliances, confectionery, mobility solutions, horology and dentistry. Switzerland was chosen for its conducive business and political environment, sophisticated infrastructure and role as a leading global innovation center.

The latter part of the visit took families through the 3-day Global Successful Transgenerational Entrepreneurship Practices (STEP) Summit bringing together researchers and practitioners from 35 academic affiliates around the globe. Themed ‘Thriving on Chaos’, participants got the opportunity to learn first-hand about the resilience of family businesses in overcoming challenges, be it at personal, family or corporate levels.

In this article, we summarize some key learnings from our visit.

Balancing innovation and tradition

On an average, Swiss family firms spend around 6% of their budget on R&D, 2 % higher than their global counterparts (Credit Suisse company data). Yet, a key characteristic of high-performing Swiss family firms is a culture deeply rooted in family values (DNA of Swiss Champions, PwC). Our first visit to V-Zug, a 100-year-old family firm was a fitting introduction to this culture of tradition-meets-innovation. Specializing in producing premium branded white goods, V-Zug has touched every second household in Switzerland through its focus on sustainability, ‘simplexity’ and innovation. Led by a non-family CEO, the founding family’s passion for quality and focus on the customer is evident in the company’s products and employees.

One factor that allows traditional family firms to constantly reinvent themselves is their ability to tap into patient capital2. Swiss chocolatier Camille Bloch for example has carved a niche for itself in the highly competitive 50-billion-dollar European chocolate industry through its focus on unique chocolate products. As the story goes, a scarcity of cocoa in the war years prompted the founder to create Ragusa, a praline-filled hazelnut treat covered in a thin layer of chocolate. Today Ragusa, along with Torino (praline-filled bars), are their two largest selling products.

Visits to fine jeweler and watch-maker Bucherer and the 150-year-old Hotel Schweizerhof in Lucern showed us that often, it is not the company’s size or R&D budget, but the management’s knowledge and the family’s motivation to succeed that drives innovation.

Taking the long-term view

The Credit Suisse Family 1000 study finds that listed family businesses in Switzerland not only outperformed local non-family firms by 9% per annum over the last decade, they also outperformed their peers globally. This, coupled with the fact that the average age of Swiss family firms is 86 years merits a discussion on factors that influence long-lasting success.

Ricardo Braglia, second-generation CEO of pharmaceutical firm Helsinn attributed their success in navigating a high-risk and rapidly-evolving environment to their long-term vision. The process of developing a drug can take up to 10 years from the research phase to market release. Over the years, Helsinn has consciously made changes to its delivery model and company structure to deliver on its dual goals of addressing unmet patient needs and maintaining profitable growth. Some measures include sustaining a strong product pipeline, developing technology through a licensing model and building a culture of corporate entrepreneurship in its employees.

A discussion on longevity is incomplete without lessons from Japanese firms who have transitioned successfully through their clear sense of purpose and appreciation of the customer’s needs. On this journey, we had the opportunity to meet the second-generation CEO of GC International, a 95-year-old Japanese firm manufacturing dental care products. After their first product launched in 1922 failed to do well, they adopted the Buddhist philosophy “SEMUI Se Mu I”3.With an emphasis on mutual benefit over product functionality, this philosophy guides all of the firm’s business and social initiatives today.

Resilience in times of chaos

A commonly quoted statistic in the family business literature is that only 30% of businesses make it to the second generation. One of the goals of the Global STEP Summit was therefore to understand what characteristics help successful family firms thrive in turbulent times. Analysis of STEP family firm data by Prof. James Davis from Utah State University showed that successful family firms pivot to regenerate advantage. Internally, a succession event or a family crisis can nudge a company to pivot. Externally, the driver could be a technological disruption or a major economic crisis.

Whatever the cause for chaos, it was evident from various panel discussions that a clarity of vision, sound governance and the ability to preempt change are key factors for success. A particularly inspiring story is that of BBX, the largest trade exchange network in the world. It was originally founded in 2002 as BarterXchange by Dr. Lee Oi Kum with the objective of being a philanthropic platform for SMEs to trade with one another. Seeking global expansion, BarterXchange joined forces with BBX, an Australian family-owned business, in 2013.

After the sudden death of the founder in 2015, Dr. Lee had to deal with the chaos of managing the business (e.g., dealing with business restructuring, lack of a succession plan), industry changes (e.g., trade industry needs with regards to global payments), and internationalization (e.g., relocating servers to cloud which is not allowed in China). Dr. Lee has thrived in chaos by being creative and open-minded to new ideas, ensuring that she knows her customers well, and learning constantly by reformatting and regrouping her knowledge capital to stay relevant.

Family is not a guarantee for continuity

According to research by the Family Firm Institute, a quarter of the family businesses that fail to transition successfully cite the lack of a proper succession plan as the key reason. The issue of succession is increasingly significant in Asia, where family businesses are younger than their American and European counterparts. Discussions at the STEP Summit stressed on the importance of good governance, developing non-family talent and an entrepreneurial vision for companies to succeed in the long-term.

A 7th generation family member from Rothschild & Co explained how their ability to think like a 200-year-old start-up has helped them constantly reinvent their business. Rothschild also creates windows of liquidity for their shareholders as a part of the agreement to allow people who are not aligned to the company vision to exit.

As a family business grows, the pool of talent within the family may be insufficient to meet business needs. Being one of the two possible family successors in the current generation, Katia Da Ros knew she had to work on governance frameworks early when she took over Irinox, a leading manufacturer of kitchen equipment in Europe. As a first step, the partners decided to have a more strategic and less operational role, opening the board to an independent director and adding two independent members in the family council. They also hired a CFO and a COO and undertook a skills evaluation exercise for all employees to understand their talent requirements better. Irinox recently became part of the Elite project of the Italian Stock Exchange, which educates companies on how to be effective and compliant as listed firms.

Swiss Champions - Locally routed, but serving their niche globally

Swiss family businesses contribute to roughly half the GDP of Switzerland and one-third of them are global players. At the Schildler AG head office in Ebikon, participants were taken through its journey of transformation from a company specializing in elevators to a global player in urban mobility solutions. From its beginnings in 1874, Schindler’s strategy of developing its core competency (control systems), entering high-growth markets early and working with local partners for expansion has helped it grow into a 25-billion-dollar company. Today Schindler has a presence in over 100 countries and caters to mobility needs of over 1 billion people per day. As we watched a film on future cities showcasing Schindler’s PORT technology4, it was hard not to marvel at the firm’s commitment to building sustainable solutions for its customers.

Every family firm we visited on this journey had its unique recipe for success. However, the common ingredient seemed to be an ability to manage business aspirations while keeping the family committed to the company’s long-term vision.

[1] Previous learning journeys took participants to Japan, San Francisco, China, Myanmar, and Johor Bahru with the goal of meeting their business counterparts and understanding the local economy.

[2] A survey by Credit Suisse of over 100 Swiss firms spread across key regions and industries showed that 70% of the companies expected to meet future funding requirements through internally generated funds compared to 47% for the overall survey.

[3] “SEMUI Se Mu I” represents a combination of values such as “selflessness, pure objectivity, charity and great wisdom” (from GC International’s corporate profile booklet).

[4] Personal Occupant Requirement Terminal (PORT) Technology is a cutting-edge intelligent transit management elevator system developed by Schindler. PORT Technology can be programmed to analyze, predict or meet individual passenger needs on elevators or other urban mobility platforms.

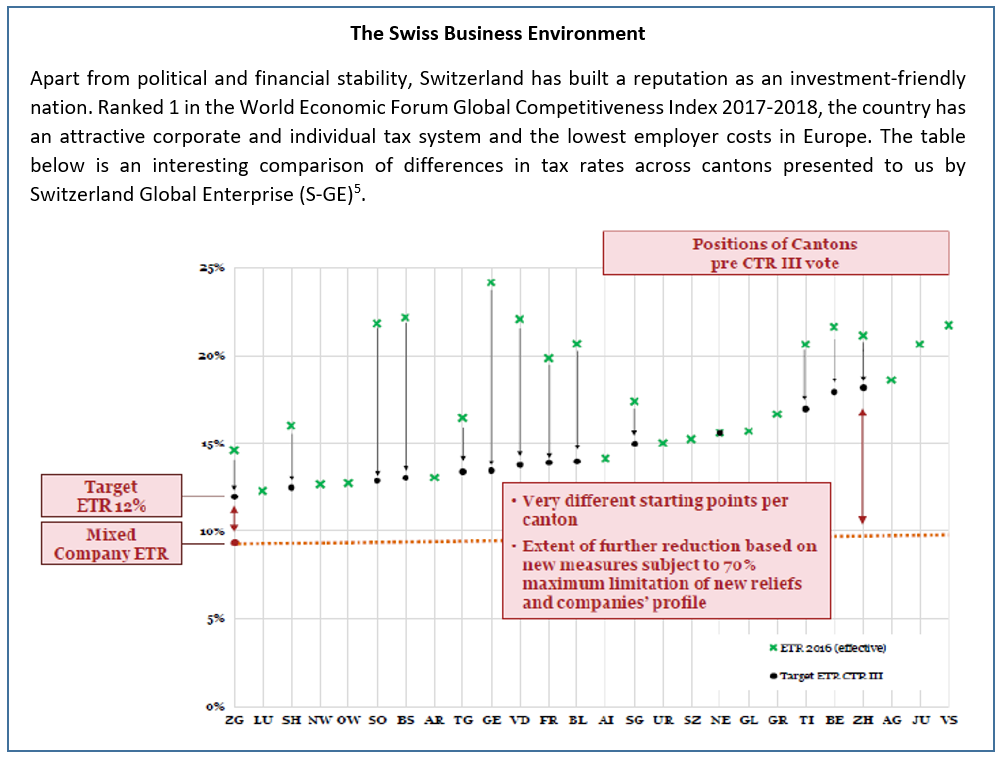

[5] On behalf of the Swiss Confederation (State Secretariat for Economic Affairs – SECO) and the Swiss cantons, S-GE promotes exports and investments by helping its clients to realize the new potential for their international businesses and thus to strengthen Switzerland as an economic hub (from S-GE website).